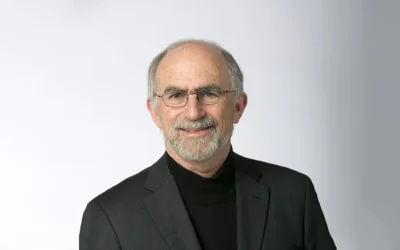

Marc Migó: “The academic and cultural environment in the U.S. values diversity and, above all, illuminates the traits that make each individual unique.”

Photography: Hans Dieter

On his 16th birthday, Marc Migó‘s grandfather gave him a very special gift: a collection of discs from the legendary classical music label Deutsche Grammophon. When he heard them, he was immediately fascinated. He had never made music, but persuaded his parents to sign him up for private classes in piano, harmony, counterpoint and composition. With professors Liliana Sainz and Xavier Boliart, he was able to attain the level required for admittance to the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya (ESMUC) in just two years. He quickly rose to prominence. With teachers such as Salvador Brotons and Albert Guinovart, Migó’s compositions were performed at international festivals such as Buffalo Festival (2014) and Charlotte New Music (2015) and won awards such as the East/West Competition Composers (2015 and 2016).

His promising career, however, took a leap forward in 2017, when he boarded a plane to New York. He had won a scholarship to study at The Juilliard School, one of the world’s most prestigious music conservatories. Today, steeped in both the Catalan and American music scenes, Migó is one of the most internationally acclaimed young Catalan composers of classical music. This June, he began a concert series at the Paranimf of the University of Barcelona (UB), which seeks to connect Catalan composers with American musical talents and which is supported by the Institute of American Studies (IEN). This month we discuss Marc’s work.

UPDATE 06.07.2023 | This June, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers of New York (ASCAP Foundation) has presented the young composer with two important awards: the Morton Gould Young Composer Award, which recognizes young talent, and the Leo Kaplan Award 2023, which has named the piece Concerto Grosso nº1 “The Seance” by Migó best composition. After receiving these awards, on June 21 he will be in Barcelona to present his Nocturne for violin, harp, piano and string orchestra, and the Concerto Grosso for flute, string orchestra and harpsichord. It will be in a very special concert, in the Paraninf of the University of Barcelona, titled From New York to Barcelona: Unsuspected Links.. At the event, Migó will share the program with Oscar winner John Coriglian, Philip Lasser and Glen Cortese, who will conduct the Orquesta del Real Círculo Artístico (ORCA).

Is it thanks to Mozart’s requiem that we’re talking to you today?

In a way, we could say so. It is a very beautiful story and, what’s more, it’s true. When I was 16, my grandfather gave me a collection of records from Deutsche Grammophon. I had never played music, but he was a very cultured person and decided it would be a good present. There were pieces by several composers. When I listened to the first record, with pieces by Bach, it did nothing for me. When I got to Mozart, however, everything changed. Specifically, with the Requiem. It was an enlightenment, a revelation, a very intense moment… A very important moment in my life. I listened to it every morning, on my 50 minute commute between home and school.

What did listening to it provoke in you?

It just opened my mind. Suddenly, in my head, melodies began to appear. Then I didn’t even have a rudimentary knowledge of music, but I was passionate. At home we had a piano. I sat there and found that I could play tunes by ear. I felt an irrevocable desire to study music.

And this is where Liliana Sainz and Xavier Boliart come into play.

Yeah. I persuaded my parents to sign me up for private classes with them. From Liliana I learned piano and harmony. From Xavier, composition. Then I didn’t know I wanted to be a musician. I was just very curious to know how everything worked. In fact, after finishing high school, I was going to go and study biology, because I loved it too, but I ended up choosing music.

What did your family say?

What did your family say?

Imagine that you’re a teenager who’s always been good at school and who, as a child, has had a strong interest in science. One day, you listen to a record and then you shut yourself up in your room, obsessed with classical music. They worried about me and I understood. Ultimately, when I finished high school, I decided to study my undergrad degree in communications and culture at the UB. I did this to give them the peace of mind that I was studying something real. But I only lasted six months. I needed to show my parents that, despite having started late in the music world, I had the talent to thrive. They listened to me and gave me their vote of confidence. I am very grateful. With a healthy dose of self-discipline and by being very methodical, I managed to cover 8 years of piano studies in just one and a half years.

You managed to enter the ESMUC in record time. How was that for you?

Before I got in, I used to go and just walk down the halls. I was so impressed by everything. I was fascinated to see the students playing. For me, getting in was confirmation that I had not yet missed the train on devoting myself to music. Once at the school, I had the feeling of being an outsider to classical music. Everyone had their friends from conservatory, from music school… And I knew no one. In fact, at choir auditions, the professor asked me what voice part I was and I didn’t know, because I had never sung in a chorus. He was pulling his hair out. Soon after, however, I began to weave a network of very important friendships, with whom I shared the same passion for music and composition.

In 2017, you received a scholarship that marked you forever.

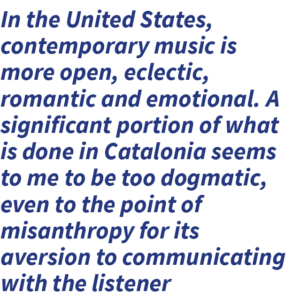

Yes. I received an SGAE scholarship to study a master’s degree in the United States. In Catalonia, the panorama of contemporary music creation seemed to me to be lacking, and I didn’t totally identify with the academic vision that it had: it was too avant-garde. In contrast, in the U.S. it was more open and eclectic, with melodies that connected more with the things that happened in the world, more romantic and more emotional. There, music was not ashamed to look for beauty. In Barcelona, on the other hand, this was seen as cheesy or tacky.

You got accepted into The Juilliard School, one of the world’s most renowned conservatories. How was it?

From the outset, I was clear that I wanted to study there, but the acceptance rate was very low: less than 5%. I didn’t want to place all my bets on that one letter, so I also applied to schools in California, Texas, Michigan, Indiana… They are also very good places. But ultimately, I was accepted at Juilliard. When I’d just landed there, I went to see a classroom where the students performed the orchestral works they had written. I flipped out. I felt a mix of panic, fear and a crazy desire to start.

What differences were there with the music education in Catalonia?

Just as New York is not the paradigm of an American city, Juilliard was not paradigm of the American conservatory either. It was a microcosm, but the best microcosm the United States could offer. It had a budget of one billion dollars and attracted incredible talent. Everyone wanted to do things. You could feel the entrepreneurial spirit that characterizes the United States. People are very responsible and have the will to excel. The academic and cultural environment in the U.S. values diversity and, above all, illuminates the traits that make each individual unique. In Barcelona, I often found myself lacking incentive.

How has studying in the United States influenced you?

How has studying in the United States influenced you?

First of all, it has given me a technical refinement of the highest level I could aspire to, contact with extraordinary musicians and a lot of opportunities. It’s widened my horizons. I have reaffirmed the idea that music is based on a bond with the audience: you need to excite them by telling stories through sound. It has given me hope for the transformative and cathartic power that art can have over people. Having lived this experience there – and having Catalan roots – has also influenced me in my compositions: they have a mixture of Mediterranean luminosity and Catalan folklore, but also American dynamism and wealth.

What knowledge is there in the United States of Catalan composers?

Very little. First of all, they have no understanding of the Catalan component. Composers such as Isaac Albéniz and Enric Granados are framed in the Spanish context. With the Ramon Llull Institute, we have organized concerts to highlight Catalan composers such as Joan Manén or Carles Suriñach and the ties they had with the United States. The American public were delighted to discover them. They were called hidden treasures. They were surprised at the quality of these composers. Catalan music culture can enrich the United States. Suddenly, by showing them these composers, you open the doors to a new corpus of excellent and little-known works.

This June, you’ll bring the music worlds of the United States and Catalonia closer together in a concert at the Paranimf at the UB, in collaboration with the IEN.

It will be on June 21st, at 19.00h. There will be a Catalan orchestra that will perform works by American composers who had links to the Catalan music scene: John Corigliano, Philip Lasser and Glen Cortese. Nocturno and Concerto Grosso No. 1 “The Seance”, two of my works will be also played. The orchestra will be conducted by a prestigious American conductor. It is the physical manifestation of the ambition to connect these two worlds.

Tap here for more information about the concert: De Nueva York en Barcelona: Vínculos insospechados

Personal website: www.marcmigo.com