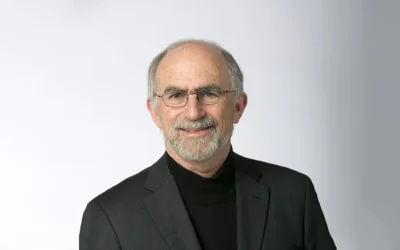

Pere Mateu Sancho: “The creation of IEN was a great step for the dissemination of astronomy and astronautics in Catalonia”.

In the early 1950s, Josep Maria Poal, a doctor, and Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich, an engineer and architect, met in New York for professional reasons. Both were amazed by North American culture and returned to Barcelona determined to create an entity that would connect Catalonia and the United States. Thus, the Institute for North American Studies was born. One of the first people to join the project was Pere Mateu Sancho.

Born in 1929 in Barcelona, Pere Mateu Sancho dedicated his entire life to the study and dissemination of astronomy and astronautics. With a degree in Space Sciences and Technologies from the Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, he was in charge of promoting activities on the disciplines of space for decades within IEN, where he was also a member of the board. He has also been a founding member of the ASTER Astronomical Association, president of the Barcelona Astronautical Weeks Organizing Committee, and a contributor to the historic weekly magazines Destino and La Vanguardia. He has participated in conferences around the world and has even published studies for NASA. In 1972, he was a member of an American scientific expedition to Antarctica.

You started talking about astronautics in Barcelona in the 1950s when few people knew what you meant. How did you become interested in this topic?

At home, my father was anti-vacation. When my brother and I were young and began our school holidays, he would encourage us to continue learning. He would buy us, among other things, the astronomy publications edited by Ignasi Puig, director of the Ebro Observatory, and I read them from cover to cover. Soon, I became very interested in everything that was explained in this and other publications. Although professionally I dedicated myself to the world of construction, the first project I collaborated on was the design of a dome for an astronomical observatory on the roof of a building on Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona.

Was spreading astronautics back then complicated?

It was not easy. Astronomy and astronautics were two disciplines that were developed, primarily, in the United States and the Soviet Union. In the 1950s, Spain was an internationally isolated country with little information from abroad. However, a group of Catalans interested in the subject decided to establish the ASTER Astronomical Association, a private entity intended to promote interest in the practice and theory of astronomy. In Catalonia, there were only two such projects: ours and the Sociedad de España y América.

Almost simultaneously, Josep Maria Poal and Josep Maria Bosch Aymerich founded the Institute of North American Studies?

Correct. In 1951, both created the IEN, with the aim of connecting the Catalan and North American cultures. Right away, the project caught the attention of various intellectuals, who were very interested in scientific, technological and cultural issues. Together, they decided they would create internal sections dedicated to studying and disseminating distinct fields. One group debated U.S. law, another investigated U.S. painting trends, and a third group inquired about new medical developments that had arised. I would like to emphasize that it is a Catalan institution, created by Catalans and without political purpose.

So, you joined to promote the sector on astronomy and astronautics. What do you remember about those early years?

Both Josep Maria Poal and I were enthusiastic about the space. In fact, we met at an exhibition organized by ASTER, at the Ateneu Barcelonès, called Space without Limits. When he contacted me offering a member position on the IEN board, I felt very fortunate. We were all eager to be able to get knowledge and information about the United States. We needed to rent a space. We found a place on Via Laietana. It was a small room where we could put a table in the center for meetings, but also where we could teach English, with the help of a teacher we hired. It is important to recall that the foreign language studied in schools back then was German. After a while, and when the project became more solidified, we moved into a flat on Valencia Street. That was our first proper base.

In 1959, President Eisenhower’s visit to Spain was a big step forward, but also for astronomy.

Very few people were prepared to hear about artificial satellites. But our conferences and exhibitions were remarkably successful; they always filled up. When Eisenhower visited Spain and embraced the Spanish authorities, the press and media began to talk more about the United States. Suddenly, the headlines and the information that came from there were more detailed.

Speaking of the press, you wrote for many years about astronomy and astronautics in the prestigious weekly magazine Destino. How was your experience?

I signed articles, many of them full-page. To me, being able to spread these disciplines seemed truly necessary. There I met Josep Pla, who had a great interest in these issues. I remember how he asked me to talk to him about artificial satellites, his curiosity on traveling through space, and the possibility of reaching other planets. During the 1960s, astronautics and astronomy were in and the space race between the United States and the USSR occupied large spaces in the media. In Barcelona, we organized a lot of conferences. The United States Consulate and the Casa Americana held us in high regard and helped by giving us interesting information. They knew we were helping to build bridges between our two cultures.

IEN specifically promoted the celebration of Valentine’s Day in Catalonia. Why is that?

In Barcelona, Valentine’s Day was rarely celebrated. We decided to popularize the holiday explaining to Catalan society what it was all about. To do this, we organized an annual event at the Ritz Hotel. Every year, it attracted more and more people, and even the press talked about it. The Institute of North American Studies was developing a solid form, but financially it was struggling. Although a lot of people wanted to study English and were interested in our events, we could not afford to continue renting a venue on Passeig de Gràcia. We discussed it with the US ambassador. We were then able to solve the problem by building the Via Augusta building. The Institute of North American Studies was truly a progressive step for the knowledge of astronautics and astronomy in Catalonia, and also in other fields.

Your passion for astronautics led you to be part of an expedition to Antarctica. How did you do it?

In the 1970s, I had produced a paper on how techniques for constructing buildings in Antarctica could also be used for construction on the Moon. I exhibited my work at an astronautics conference in Brussels, and the members of the US delegation took notice of it. They were very interested in the subject, and they realized that they could leverage some of the money they were investing in space research to establish bases in Antarctica. I accompanied them on a month-long expedition. It was spectacular. We crossed the polar cap. It is the most fabulous and unique place I have ever seen in my life. It was still about ten years before Spain inaugurated its first base.

Do you think man will soon be able to set foot on the Moon again?

Man’s return to the Moon is almost a certainty. I, who am 93 years old, may not see it, but if I lived a few more years, I would surely witness it. The important challenge now is to be able to go to Mars. That will be complicated…